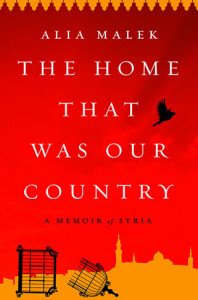

Sarika Mehta talks to author Alia Malek about her memoir The Home That Was Our Country...about Syria's history and contemporary politics through stories of her own family

from the NYT:

"Alia Malek’s memoir, “The Home That Was Our Country,” is one of the finest examples of this new testimonial writing. Born in Baltimore to Syrian-American parents, Malek is a journalist and attorney who landed a job in the civil rights division of the Justice Department less than a year before 9/11. Unable to endure the political climate under President George W. Bush, she quit the United States for the Middle East, where she traveled and taught human rights for the better part of a decade. Her political and cultural fluency, as well as her deep familiarity with the landscape, allow her to become “a human ear” as Svetlana Alexievich calls it, recording the tragic absurdities of daily life that give way to dark humor. On an earlier trip, she had visited southern Lebanon and toured a prison that was recently closed. Her guide, a former inmate, instructed the group’s members to cover their noses and mouths, “so as not to inhale the germs of diseases that he was convinced still lingered.” The disease that lingered, of course, was despair. She spotted a sign for the “suffering yard” — suffering, she writes, “was their translation for torture.”

In April 2011, Malek moved to the Syrian capital of Damascus to report in secret for The Nation and The New York Times. The country was in the initial throes of what many hoped would become a democratic uprising born out of the Arab Spring. Yet there were already terrible signs that the regime of Bashar al-Assad wasn’t going to give up without bloody reprisals. In February, his security forces had rounded up and tortured at least 15 children for anti-Assad graffiti in their town of Dara’a. Ordinary Syrians, long oppressed by two generations of the Assad family’s brutality, were taking to the streets in protest. In an attempt to quell reports of dissent, the regime banned many foreign journalists. Malek went to work anyway. As a cover story, she tells her Syrian cousins that she’s writing a book about her maternal grandmother, Salma, the daughter of a Christian businessman, Sheikh Abdeljawwad al-Mir, born in the Ottoman Empire in 1889.

Her cover story wasn’t entirely false, as that book becomes this one, and Malek grounds her narrative throughout in her grandmother’s story. Salma, a charismatic and embittered matriarch, grew up as the chain-smoking daughter in a family that prized only men, and after suffering a stroke, spends the last seven years of her life in her Damascus apartment, “locked in” her body, paralyzed yet alert, able to communicate only with her eyes. When Salma dies, she leaves behind a chic flat for Malek’s family, which, after decades of feuding with a hostile tenant, they succeed in reclaiming.

As Syria burns, it falls to Malek to renovate the flat — haggling for light fixtures from the Electricity Souk during a blackout, and keeping an eye on a corrupt contractor while the Assad regime gasses its own people, drops barrel bombs — oil drums loaded with shrapnel — from helicopters, and disappears thousands to be tortured in underground prisons.

Malek observes almost none of this firsthand. Instead, her war is largely made up of what she can’t see. She lives day to day under the cloud of claustrophobia and menace that dominates the Syrian capital, where her presence poses a significant risk both to herself and to her Syrian family. Attempting, at one point, to communicate to Malek the kind of danger she’s putting her family in, a beloved cousin grabs her own hair, imitating the treatment the security forces mete out upon women, which can include gang rape. “That’s what they will do,” she tells Malek. “They will take all of us if you do something.”"