Clayton Morgareidge comments on what we learn about the control of space in Portland from how the city is dealing with unhoused people living along the Springwater Corridor and from the plan to house them in a warehouse at Terminal One.

Photo Credit: northparkblocks.org

Homeless in Portland

Anyone who lives in Portland can’t help seeing a lot of people who have no roofs over their heads other than a tarp or a tent. There are three or four thousand people, men and women, children and old people, families, couples, and solitary individuals, bodies and minds in all conditions of health and illness. They are camped on sidewalks, in parks, in various enclaves more or less, and for the moment, permitted by the authorities. Some four or five hundred are living along the Springwater bike and hiking trail that runs through southeast Portland. We might think of these people as exiled from the supporting institutions the rest of us mostly take for granted, namely employment with a living wage or some other regular and adequate income, comfortable housing with electricity and running water at our fingertips, sewer and garbage service we rarely have to think about, bank accounts, access to medical and dental care when we need it, and networks of friends and family who are also similarly grounded in the world. The people living in tents and tarps and sleeping bags are excluded from all that. In the sense that the rest of us are at home in this society – at least until the next big recession or major personal catastrophe, the people I have called exiled are not at home in our world, i.e. are homeless.

Many of them do what they can to support each other. They get sporadic and generally inadequate help from a tangle of government and charitable services that are often complicated, bureaucratic, hard to find, and dependent on the shifting tides of money and politics.

It’s inevitable that a mass of people who, though they share our cityscape, are exiled from the social network that supports us, will disturb the peace in a variety of ways. The spaces we use for recreation or for getting from A to B are now the living space for people whose garbage is not automatically picked up every week, whose private bathroom is not just down the hall, and who have few options for how to spend their days where they are welcome or needed as we are when we go to work or hang out in coffee shops with our friends or our laptops. So business owners ask the authorities to remove street people from the sidewalks. Home owners, like those along the Springwater Corridor, want campers swept from the neighborhood. And that’s natural enough: displaced people are visibly and audibly needy and unhappy. They disrupt the mood and the ordinary activities of those of us who are at home in society. Most settled people don’t want to confront unwashed hands begging for spare change by their sidewalk tables in the Pearl or to find human feces in their back yards.

So what is being done? Let me focus on two items currently in the public eye. First, there is the decision by Mayor Charlie Hales to clear out all of the four or five hundred campers along the Springwater Corridor. Hales first scheduled it for August 1, but after protests by supporters of the unhoused, he deferred it to September 1. The community of Springwater campers met in July and made a number of demands to the City, including not sweeping the trail on August 1, that people be not just displaced and left to scrounge for another spot, but relocated to identified places with facilities including storage units; that the city make accommodations for the disabled, the elderly, the sick, and people with small children; that the police stop seizing their possessions and criminalizing homelessness, and that the Mayor meet with the people affected to discuss options.

There is also the proposal, just passed by the City Council, to turn the fourteen acre industrial site on NW Front Avenue known as Terminal One with its vacant warehouse into a temporary shelter for 400 homeless people. There are a multitude of bureaucratic problems with funding and implementing this proposal. From the point of view of the people who might be relocated to the site, it’s a long way from stores and health services. The public transportation is inadequate. Because of high speed traffic and poorly lit intersections, it’s not suitable for pedestrians. And it’s not clear that the kinds of services will be provided that will make this giant warehouse any thing more than just a warehouse for sequestering the people that well-off folk don’t want to run into where they are doing business and living their genteel lives.

So the question is who gets to go where and do what in the space that is the city of Portland. It’s a matter of money and property. If you own property, you can determine who gets to use it and what others have to pay to use it. If you have a lot of money, then you can buy property to live in, and you can buy property that those without property can live in by paying you rent. If you have some money, you can live in a place where you can afford the rent. If you have very little money, like someone living on the minimum wage, you may or not be able to find a place to live. And if you have no money, or almost none, then you just have to find a place where for one reason or another, at least for the moment, no one will evict you. You are living outside the system of permissions granted by money. Money is the ticket to ride, to live. Without a ticket you are on the outside, or rather you find someplace on the inside where no one is watching…or no one with the power to make you move is around – like along the Springwater Corridor until September 1. It is the job of city and county government to enforce these rules, to see that property rights are protected from those with no property and therefore no right to space.

It was observed a long time ago that “The executive of the modern State is but a committee for managing the common affairs of the [owners of capital] (= “the whole bourgeoisie”).”[1] The same must be said of our city government. It does not manage the common affairs of all of us. The officials of the city consult with the most propertied citizens about how to best protect them from those with no property. For now, they seem to have decided that maybe those with no property should be put in an old warehouse away from downtown and the upscale Pearl.

The sanctity of property is perhaps the dominant social and political principle of our world. Sometime its managers have to restrict the freedom of some property in order to keep the system running smoothly – for example by giving up the money that could be made by selling Terminal One so some of the unhoused can be isolated there. Sometimes the people with no property can organize to make enough noise that that property must make some concessions, as when the tenants of a Portland apartment house facing massive and immediate rent increases formed a union and the managers gave the tenants more time before deciding whether to move or pay the higher rent. But the propertied and the unpropertied will only be treated equally when the basic laws of our system change making it impossible to control for one’s own private benefit the spaces in which people need to live.

[1] Marx and Engles, Communist Manifesto, Section 1.

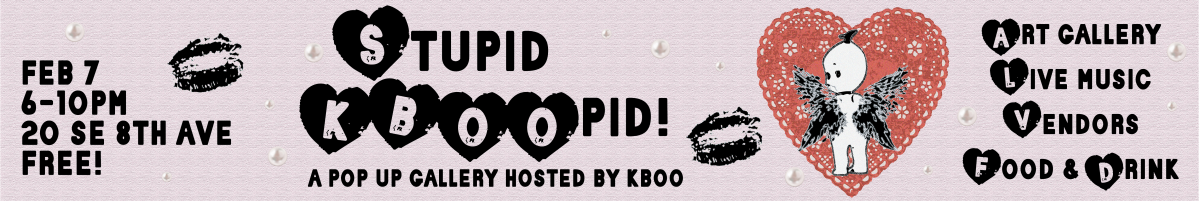

- KBOO